Merge across repositories - Git.

31 Oct 2018** TL;DR - Skip straight to the last two sections.

We all know that Git is an excellent piece of software and it is a DVCS and the D stands for 'Distributed' and all of that is very good and so on and so forth, etc.

But honestly, how often do you use the 'D' part in there?

The 'D' in DVCS. A short detour!

Digressing a bit. Once upon a time when I was young, in programming or otherwise, I needed to handle distributed transactions. In the Microsoft world it meant DTC - the Distributed Transaction Coordinator and I didn't know squat-jack about that. So I walked up to the venerable senior architect in the organization and asked for help. His terse response - 'Change the system so that you don't need it !'. I was quite taken aback then, given that my naive faith in the power of tools had not yet been battle-tested.

Over the years, this recurred once, then again, and again, and by now I have learned, both the hard way and the soft way, that the 'D' basically means - 'Don't go there. There be Dragons !!! '.

So back to the point - how do we use Git most often?

How do we use Git? Usually, mostly, as a better VCS.

In my experience, it works mostly as a drop in replacement for a standard VCS.

Oh yes, it comes with value adds:

- Robust behavior

- Fast - try branching or checking out a big repo from Git vs SVN/VSTS.

- Cheap feature branches.

But mostly, in spite of all the distribu-thing-ummajigs in there, we still have a central source of truth.

Somewhere out there is a 'master' which is 'THE master' branch. And while we branch and fork and checkout and checkin and switch and 'pull request' all we like, sooner or later, all roads lead back to Rome - which in this case - is that particular 'THE master'.

Short detour again - introducing Robert Frost !

Do you know this Frost?

No? Ok, let me introduce you. The chief characteristic of the esteemed Mr. Frost is his rather well known penchant of taking the road less tavelled by. (Murphy must have been quite a fan !).

Point being, sometimes, Mr. Frost steps into the fray, and as is his wont, takes the road less travelled by, and pulls you along into it.

Road less travelled - Using Git as a "DVCS".

So finally, after several years of using Git as a VCS with a first name ("D"), I finally have a situation where I have to deal with the "Distributed" nature of Git.

The context, and the problem.

Let me explain the situation. In this here and now, this is how the cookie crumbled.

In my current engagement, work occurs in two Git repositories - In two Git repositories - each with its own 'master' branch and feature branches and history and so on.

Why so? Well, because,

- The work is explorative in nature.

- And there are multiple tracks of work for separate goals.

Moreover,

- Many tracks of work DO NOT have a deadline. It could be from 'weeks' to 'years'.

- Many of them MAY never become production code. Production happens when certain conditions become evident.

And the explorative work has way more volume than actual production work. So to cleanly enforce separation of code, there are two repositories -

-

Repo Prod - The production code repository.

- This is code that will go to production at some point. All code here has to be of production quality, with tests, automated CI/CD pipelines etc. Not all of them, however, are in the 'master', or 'source of truth' branch.

-

Repo ConDev - The concept development repository.

- Again lots of branches, with master, and feature branches, and spikes, and prospective candidates for production, and abandoned work and so on. As the name indicates, it is for concept development.

- rules/coding guidelines/practises are a lot more lax here. Essentially, this if for feasibility studies, investigative work and other POCs (Proof-Of-Concept).

But every now and then, a POC clears business validation.

Subsequently, a new branch in created in the POC repo, within which the concept based code is upgraded and polished, and code quality reviews and all of the other practises which production readiness demands happen.

Once that is done, though, what we have is this nice, freshly minted, production quality sub-system residing in branch 'nice-production-quality-sub-system' in repository 'POC'.

What we need, however, is the above code sitting in branch 'checked-in-production-sub-system' in repository 'Prod' - along with its long history of development in the 'POC' repo.

Thus what I have to do is move the code across git repositories, preserving history.

Eh! WHAT?

The theory - Git merge across repositories.

What is the first thing to do when you have something like this? Well, you look for volunteers. There are none. Ok, So someone must have done this before? Oops ! Double or nothing, its nobody again. Thus at this point, after successfully drawing two blanks, you go back to the drawing board and start doodling.

Which is when it hits you. Git is designed to do exactly that - it is, after all, a distributed VCS.

All version control systems have this concept of 'local repository' and 'remote repository'. The way you work, is that you make all changes in your local copy, and when it is done you check in into local. This local is something on your local physical machine. and at this point - only your copy has your changes.

But usually you want to synchronize things, Not just make endless changes to the same thing (repository). And synchronize implicitly means you needs two things to synchronize between - a 'source' and a 'sink'.

From wikipedia -

Distributed revision control systems (DVCS) takes a peer-to-peer approach to version control, as opposed to the client–server approach of centralized systems. Distributed revision control synchronizes repositories by exchanging patches from peer to peer. There is no single central version of the codebase; instead, each user has a working copy and the full change history.

And here is the trick that actually lets us do what we want.

In traditional or client-server based synchronization, you can only synchronize from the 'sink' to the 'source'. The 'sink' can keep changing its contents, and you can have many 'sink's, but every single 'sink' needs to pass all its changes/records to the 'source' for synchronization to be effective and available to all other 'sink's. And these synchronization steps are all sequential. The 'source' is the gatekeeper, and cannot be changed.

Git, however, eliminates the difference between 'source' and 'sink' - 'source' and 'sink' are just roles you play. Moreover, any repository can choose any other repository, and between those two, either party may play the role of 'source' or 'sink' at will.

Some taxonomy now - In Git - the 'sink' is called the 'local' repo. The 'source' is called the 'remote'. And in Git or other DVCSs it is possible to switch out the 'remote' to some other 'remote', or have any number of 'remote's.

On that principle, if I fetch the 'prod-ready-poc' branch from the 'POC' remote into the 'POC' local repo, then switch (or actually, add) the 'Prod' remote as another 'source' (call it 'newremote'), it should theoretically be possible to push the now local 'prod-ready-poc' branch from 'POC' local into a new branch (call it 'new-in-prod'), on the 'Prod' remote (i.e. the 'newremote' added to 'POC local').

Git should seamlessly merge both. Or that's the theory anyway.

A complete discussion of why is beyond the scope of this post - but if you are interested you can get started with git basics. Another good source is here

Walking the talk - Git merge across repositories.

But theory and practise are very different things, so let's see what it takes to put theory into practise.

Arrange

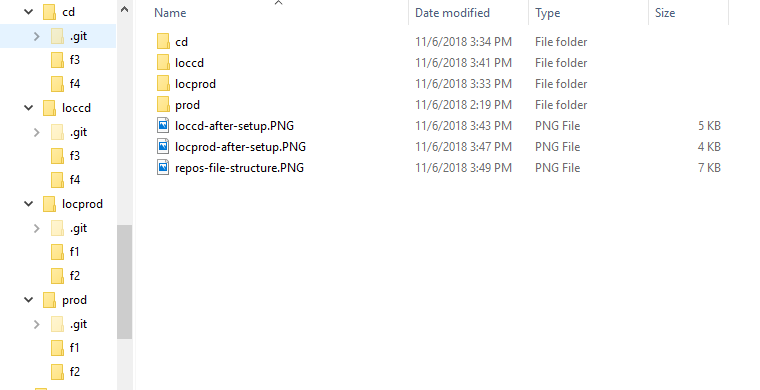

- Create two repositories in some remote location - 'prod' and 'cd'. Each with just the master branch.

For my purposes, everything is setup on local machine - since we need a total of 4, prod, prod local copy, condev, condev local copy - all 4 instances of the git repos have been setup on the file system. After setup, it looks like

- Work with 'prod'

- Get 'prod' onto local machine - 'locprod'.

- Add folder 'f1' and 'f2' to 'master' in 'locprod'.

- Add files 'f11' and 'f21' to 'master' in 'locprod'.

- Create branch 'pb' in 'locprod' from 'master'.

- push 'pb' from 'locprod' to 'prod'.

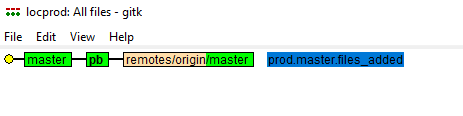

After setup, the history for branch 'pb' from 'locprod'

- Now work with 'cd'

- Get 'cd' onto local machine - 'loccd'.

- Add folder 'f3' and 'f4' to 'master' in 'lcocd'.

- Add files 'f31' and 'f41' to 'master' in 'loccd'.

- Create branch 'cdb' in 'loccd' from 'master'.

- push 'cdb' from 'loccd' to 'cd'.

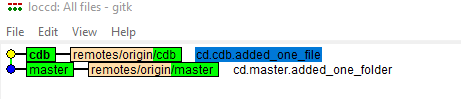

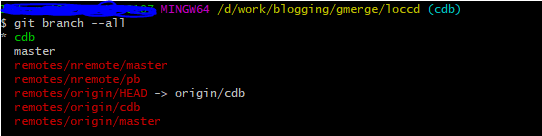

And branch 'cdb' history from 'loccd'

At this point we have two repositories with branches whose histories have diverged. The goal is to get all the contents and history of 'cdb' in 'loccd' into 'pb' in 'prod'. Which means, at the end, the 'pb' branch in 'prod' should contain all the four folders 'f1', 'f2', 'f3', 'f4' with all of their files, and the history of branch 'pb' should contain all of the individual commit/operation logs from 'prod'/'locprod' and 'cd'/'loccd'.

I am not showing the steps for the above because if you need help here, you are really not ready for the next bits.

Act

The goal here is to merge 'loccd'.'cdb' into, ultimately, 'prod'.'pb'. However, this is a multi-step process.

-

While on bash in 'locprod'.'master', add a new EMPTY branch 'tmp' in 'locprod'

git checkout --orphan tmp -

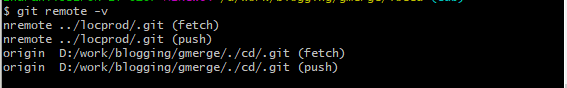

Switch to bash on 'loccd'. Add 'locprod' as a new remote repo for 'loccd'. Name this remote as 'nremote'.

git remote add nremote /full/file/path/to/gitrepo/.gitTo verify remotes are setup, rungit remote -v. On my machine, I see

-

Fetch all from the newly configured remote.

git fetch nremoteViewing list of branches now shows

-

Create new branch 'loccd'.'tmp' from 'loccd'.'cdb'

git checkout -b tmp -

Set it to track the branch 'tmp' on 'locprod'.

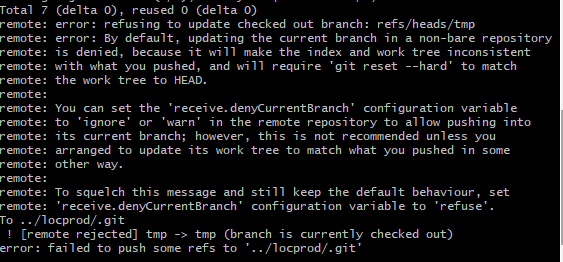

git push -u nremote tmp. Ensure that the target branch is not open -i.e. 'tmp' is not the currently checked out branch for 'locprod'. If so, this is the error Switch to some other branch. Once this step is successfull you have the 'loccd'.'tmp' data in 'locprod'.'tmp'.

Switch to some other branch. Once this step is successfull you have the 'loccd'.'tmp' data in 'locprod'.'tmp'. -

Go to bash on 'loccd'.'tmp' and merge 'loccd'.'cdb' into 'loccd'.'tmp'. Assuming you are on the 'tmp' branch in bash, run

git push nremote tmp --allow-unrelated-histories. Note the flag. Once past this step, 'locprod'.'tmp' should have everything from 'prod'.'pb' and 'locprod'.'cdb', including histories. -

Push everything back into 'prod'.'tmp'. Since 'tmp' was created in 'locprod', it doesn't exist yet in 'prod', so you need to set the upstream tracking info.

git push -u origin tmpcreates the branch if it doesnt exist and starts tracking. -

Switch bash to 'locprod'.'pb'. Reverse merge 'locprod'.'tmp' into 'locprod'.'pb'.

git merge tmp. This should be seamless.

Assert

And you are done.

These are the final folders

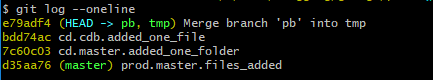

This is the final log of history

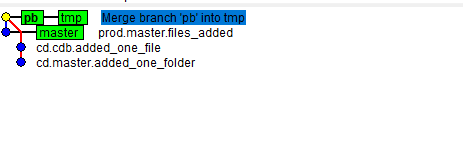

And the final git merge

- Some Notes

- Everything from both repos is merged and available in 'prod.pb'.

- There may be a few redundant steps in between, but I was gunning for a solution where, in case of issues, I could just delete stuff and restart - hence all thise temporary branches. It could conceivably work without those, but your mileage may vary.

- One precaution - Always work off clean branches with no pending changes. Stage or commit everything before starting on this.

Thats it. You are just one step away from having everything in 'prod'.'master' by merging 'prod.pb' into 'prod'.'master'. Which you can do by whatever method works best for you - review, merge, push, pull-request whatever.

This is what worked for me. Thank you for reading. Have a nice day!

Insen

Insen