Hello SARG ! Let's index and tune a SQL!

12 Apr 2018No, Not your Beetle Bailey Sarge ! Focus !! Here we have composite keys and query plans and cryptic acronyms all playing ball really well together, only in their own fashion, much like today's unsupervised machine learning methods which nobody really understands.

The pole position ('Pole Problem'??).

The story begins with LINQ and composite keys in EF. (in fact, many programmer stories usually begin with LINQ. It’s a veritable treasure trove of stories). So one day I needed the LINQ equivalent of a SQL IN query for a composite keyed table. That's what started this whole SARG thing.

Consider a table with a single column primary key called Id. The query to get records with a IN clause via LINQ is this

from entity in db.Table

where computedList.Contains(entity.Id)

select x.

Therefore, extrapolating merrily, you reason that tables with Composite keys would need a join as you can't match multiple values in the contains option. And so you write

from entity in db.Table

join pair in locals

on new { entity.Id1, entity.Id2 }

equals new { Id1 = pair.Item1, Id2 = pair.Item2 }

select entity

Boom! Error message 101. ( ps. Did you ever hear that joke about the guy who wanted to write great things, move people to joy and tears through his words and ended up writing error messages for Microsoft). Here is an example in action - the result of executing the above LINQ is an error ending with ...Only primitive types or enumeration types are supported in this context..

What it means here is EF and SQL Server have no idea how to join a table in database with a list in memory. It cannot be done. You can either have a SQL query (generated through the IQueryable implementation of LINQ) or you fetch all database data into memory and then do the join. The latter is a very bad idea in a table with even 200000 rows, let alone millions.

So how do you write the LINQ such that you get SQL which runs in SQL server? Turns out that this problem is quite intractable, with no elegant solutions.

You have one SQL equivalent which uses LINQ's 'Contains' option awkwardly

from entity in db.Table

where computed.Contains("Id1=" + entity.Id1 + "," + "Id2=" + entity.Id2)

select entity

In this case, you have created your list 'computed' with key values which are a concatenation of all key columns as strings. In your LINQ query, you create equivalent keys from all of the database rows and compare this generated key with your predefined list. This generates a SQL of the sort

Select * from Table

Where ("Id1=" + Id1 + "," + "Id2=" + Id2)

in ( "Id1=Id1,Id2=Id2", "Id1=Id91,Id2=Id92")

Note: Not exact, but that’s handwritten un-compiled SQL, so there may be issues, but you get the drift.

This is messy. But that is not the main problem. Quoting from Stack Overflow - "a more important problem is that this solution is not sargable, which means: it bypasses any database indexes on Id1 and Id2 that could have been used otherwise. This will perform very very poorly."

Note: For an in-depth discussion of Composite Keys and EF ad the general recommended ways of handling them check either this Stack Overflow question or this link.

Enter the SARG !

I had encountered this SARG before, but had forgotten the details of it, so had to look it up. Turns out SARGability is a big deal in SQL server and other RDBMSs.

So what is SARG? It’s an acronym word derived from Search and Argument. An alternative usage is SARGable, which means 'Search Argument Able'. As per Wikipedia SARGable is defined as 'In relational databases, a condition (or predicate) in a query is said to be sargable if the DBMS engine can take advantage of an index to speed up the execution of the query'.

A technical definition would be 'Sargability is the query's ability to traverse the b-tree index using the binary search method that relies on half-set elimination for the sorted items array. In SQL, it would be displayed on the execution plan as a "index seek".'

Now why is this important?

Because indexes are key to fast and efficient RDBMS queries and stored procedures. Note: At this point, if you are not interested in fast and efficient database queries, you can now go read something else. For the rest however, hopefully this will help.

Databases have Indexes. In fact so important and ubiquitous are database indexes that RDBMSs create all manner of indexes automatically for you. Primary Keys, Foreign Keys, Unique contraints - all are indexes created silently behind the scenes in any respectable database. However, indexes are no good if your query cannot take advantage of them. That is where SARGability comes in.

IMPORTANT NOTE - A non sargable query will not use your indexes.

Instead it will fall back to index scans and table scans, for indexed and non-indexed tables respectively, instead of index seeks, and it will do so all of the time, destroying the entire purpose of indexes and our goal of fast efficient queries.

To understand why this happens, we will look at a simple but oft-repeated SQL need. Consider a table called Customer with an primary key fields - Id, and a LastName varchar column with an index on it. We need to retrieve Customers whose last name is Smith.

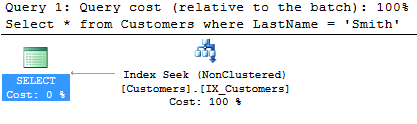

Here are two simple queries which can do this and their query plans

Option 1

1. Select * from Customer where LastName = 'Smith'

.

.

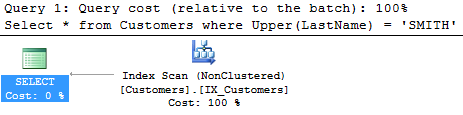

Option 2

2. Select * from Customer where Upper(LastName) = 'SMITH'

.

.

See what happened? The query plan changed from index seek to index scan.

In this case my table had two columns, with indexes defined on each. A primary key on Id, a non-primary index on LastName and still we go from index seek to index scan.

Why does this happen? A tale Of B-Trees and Database Indexes.

A database is basically like a giant dictionary, with its pages shuffled. The index at the back lists the start word per page number, and each page is numbered. Moreover, more pages are being continuously added or removed, so the index at the back needs to be constantly maintained. But there is an extra twist. The index pages are themselves jumbled. So while the index keeps track of whats where in the main pages, we have to keep track of the index pages itself. The database depends on keeping rows in logical order by virtue of its keys, separate from physical order. However, that does not mean that all of those rows are in the same contiguous order on disc. The database also depends on keeping its physical order separate from its logical order. This is essentially what a RDBMS index does. The mechanism used to implement all of this consists of a doubly linked list, a B-Tree and a fetch process.

Doubly linked list

The logical sequence is established between leaf index nodes through a doubly linked list. Each node points to a database block and to its previous and next block. Each page stores as many index entries as possible. Thus there is two layer ordering, across nodes followed by within nodes. Note the sequential entries in an index leaf node has no guarantee of sequential entries on disk or on database blocks. They could be pointing to different areas of physical storage.

B-Tree - the Balanced Tree in DBMS.

Now for the operating system each page is in random order on disk. To find the database block pages, the database uses what is called as B-Tree, or Balanced Tree. (No, it is not binary tree; At the least, its an n-ary tree, with n variable). In a B-Tree, each branch node consists of the starting entries of the set of leaf nodes it covers. Since it is also a database block in itself, it is quite large and in sorted order of leaf node entries. Thus each entry in each branch node has the starting value(s, if composite key) of the indexed column of the leaf node and the leaf node's location on disk. An index B-Tree is initially built in such a way that all leaf nodes are covered by a branch node. New layers of branches are created until a branch contains enough information to enable traversing down to the leaf node with the desired index column values and fits in a single database page block. This is constantly maintained. A characteristic of this B-Tree is that all elements can be accessed with the same number of steps, and the depth can change based on the size of the database page block being used by the database to store data.

The fetch.

There are a few different ways for a database to approach fetching the data.

The index seek.

The act of reaching for a row data in a particular table based on a given index i.e, you are given the column values to search for, involves the following steps. The database looks up the index and its root page, traverses the page until it finds a branch node whose range covers these keys values, goes deeper one layer, recursively does the same until it finds the leaf node which contains the given keys. Once the leaf node is found, it is iterated/searched until the specific row/key values are reached. This key points to the database block which stores the table data on the heap. Now corresponding data can be fetched if needed, since it depends on the query.

The index scan.

Index Scan is nothing but scanning on the data pages from the first page to the last page. If there is an index on a table, and if the query is touching a larger amount of data, which means the query is retrieving more than 50 percent or 90 percent of the data, and then the optimizer would just scan all the data pages to retrieve the data rows.

The table scan.

If there is no index, then you might see a Table Scan in the execution plan. A Table scan touches all database blocks and rows for the table as it doesn't have the aid of an index's B-Tree.

So, why 'index seek' to 'index scan'?

So, coming back to the question - Why did the query plan change from index seek to index scan?

Well, because, in our case the index key was defined on column 'LastName'. So the index had the key 'Smith' somewhere - root, branch or leaf node. However, 'SMITH' was not a value which was present in the index. So a full scan of all table rows, using the index on LastName would be needed, as the Sql optimiser cannot be sure of the data until the string is manually compared, for which it needs to physically read in the table row data from the database block on disk.

In real world scenarios, with multiple tables, joins and complex clauses and functions, a predicate (where clause) or join condition can easily go from a index seek to an index scan to a table scan.

SARGability thus greatly determines the choice of indexing used , OR not used, and has a direct impact on the query execution time.

Breaking SARGability and how to fix.

Many scenarios break SARGability. General thumbrules of breaking SARGability and things not to do include -

Implicit/explicit datatype conversion before comparision

Given that column B is defined as a varchar.

Select * from F WHERE B = 1

is not sargable. Do the following instead.

Select * from F WHERE B = '1'

Applying functions/operations to indexed columns before comparisions or joins.

In the following case,

Select * from F where DateDiff(day, ODate, GetDate()) > 7

is bad. The SQL optimizer can't use an index on the field, even if one exists. It will literally have to evaluate this function for every row of the table. The better option is to have only the ODate column in where clause. A rewrite would look like this -

Select * from F where ODate >= DateAdd(day, -7, Cast(GetDate() as Date))

Basically, If possible, use functions in reverse. Instead of WHERE FUNCTION(Field) = 'BLAH', do WHERE Field = INVERSE_FUNCTION('BLAH').

Other examples -

Bad: Select ... WHERE isNull(FullName,'Ed Jones') = 'Ed Jones'

Fixed: Select ... WHERE ((FullName = 'Ed Jones') OR (FullName IS NULL)) (Note that this is bad for other reasons - not being able to cache a query plan).

Bad: Select ... WHERE SUBSTRING(DealerName,4) = 'Ford'

Fixed: Select ... WHERE DealerName Like 'Ford%'

Bad: SELECT ...WHERE Number + 0 = 42

Fixed: SELECT ...WHERE Number = 42 - 0

Note: Read somewhere that An explicit CAST of a DATE column to DATETIME still leaves the predicate SARGable. This is an exception that’s been specifically coded into the optimiser. Not verified though.

Wild-cards

Leading on from the substring query in the list just above, do you see the wildcard in

Select ... WHERE Manufacturer Like 'Ford%'

Note that the wildcard is NOT a leading wildcard. Leading wildcards are bad. The following is bad.

Select ... WHERE Manufacturer Like '%ord%'

This basically turns the query into a full-text search query with an index scan, or worse, a table scan.

Tip : Indexes on computed columns.

Sometimes the use of functions and so on is unavoidable. The general solution is to add a calculated column for the field value returned by the function and then create a non-clustered index for that calculated column.

Note that this computed column does not need to be persisted. Consider the query

SELECT LastName FROM Customers where LEFT(LastName,1)='K'

In this case, add a computed column 'LastNameStartsWith' to hold Left(LastName, 1), and add a non-clustered index on 'LastNameStartWith'.

Be aware that this is a double edged sword however, as you may end up creating lots of indexes for every use combination. Each new index needs to be maintained continuously by the database and ultimately may be counter effective. Be discreet.

Hope this helped. Good luck with the queries.

Insen

Insen